Author:

Seneca the Younger

Almost ready!

In order to save audiobooks to your Wish List you must be signed in to your account.

Log in Create account

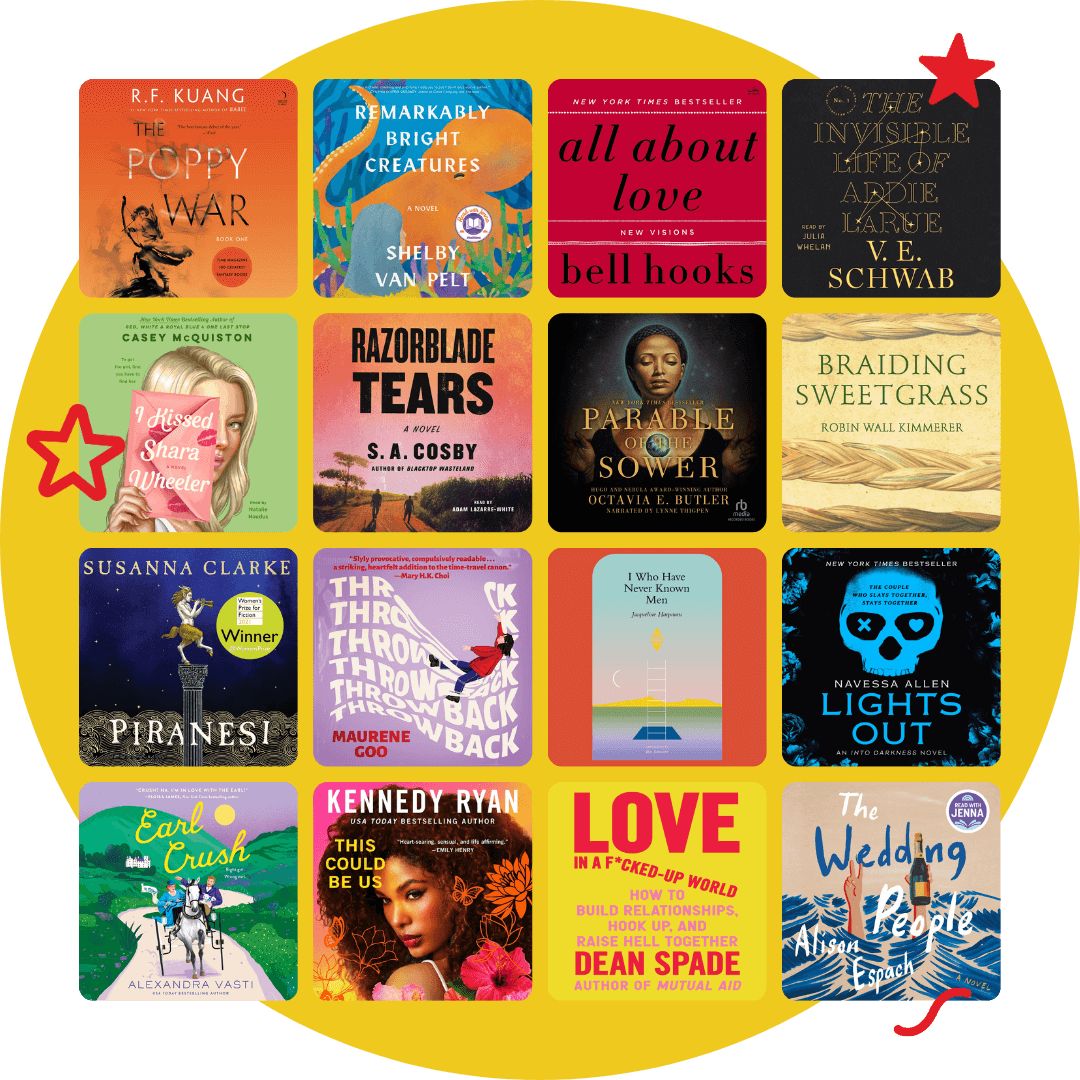

Indie Bookshop Appreciation Sale

In celebration of indies everywhere, shop our limited-time sale on bestselling audiobooks. Don’t miss out—purchases support local bookstores!

Shop the saleOf Consolation

This audiobook uses AI narration.

We’re taking steps to make sure AI narration is transparent.

Learn moreSummary

These three ‘Consolations’, written by Seneca to his mother and two friends, have been described as ‘the crowning achievement in the canon of ‘consolation letters’. But sentimental they are not, for they emerge from the writer’s deep-seated commitment to Stoicism, where individuals are exhorted to inhabit qualities of virtue, positivity, resilience, and indifference. This recording opens with Seneca’s consolatory letter to Marcia, who, after three years, was still mourning the death of her son. He recognises her exceptional personal qualities and what benefits she has brought to her family, having rescued her father’s legacy as a historian following his death. He cites other noble Roman mothers who lost their sons, and enjoins her to adopt a more Stoic attitude of mind: we are all destined to die, he declares.

The second letter is to his mother sent after he had been exiled to Corsica by Emperor Caligula. He counsels Helvia not to mourn his absence – not least because he himself does not feel grief at the prospect of his own exile. He acknowledges the trials of his mother during her life, remarking ‘ill-fortune has given you no respite’. But her grief at the absence of her son may be put to one side in the knowledge that as he has ‘never trusted in Fortune,’ she can be comforted that her son is not discommoded. And history points to far harsher separations.

The final letter is to Polybius, Emperor Claudius’s Literary Secretary, who was mourning his brother. Written while in exile, Seneca’s unwavering commitment to Stoic philosophy is again in evidence. One of Seneca’s principal suggestions is for Polybius to distract himself from grief by an increasing involvement in work.

These ‘Consolations’ have been widely admired from Classical times to the present, but are periodically questioned for their emphasis on a somewhat detached approach to grief and bereavement. Not all can manage imperturbability in such circumstances. Nevertheless, there is a steadiness and emotional calm in these missives, which Seneca himself displayed when ordered to commit suicide by Emperor Nero.

Audiobook details

Narrator:

Mike Rogers

ISBN:

9781004138456

Length:

3 hours 57 minutes

Language:

English

Publisher:

W. F. Howes Ltd

Publication date:

July 20, 2023

Edition:

Unabridged

Start gifting

Start gifting

Libro.fm for Business

Libro.fm for Business

Start a membership, get two free audiobooks

Start a membership, get two free audiobooks